Department of Civil Imagination

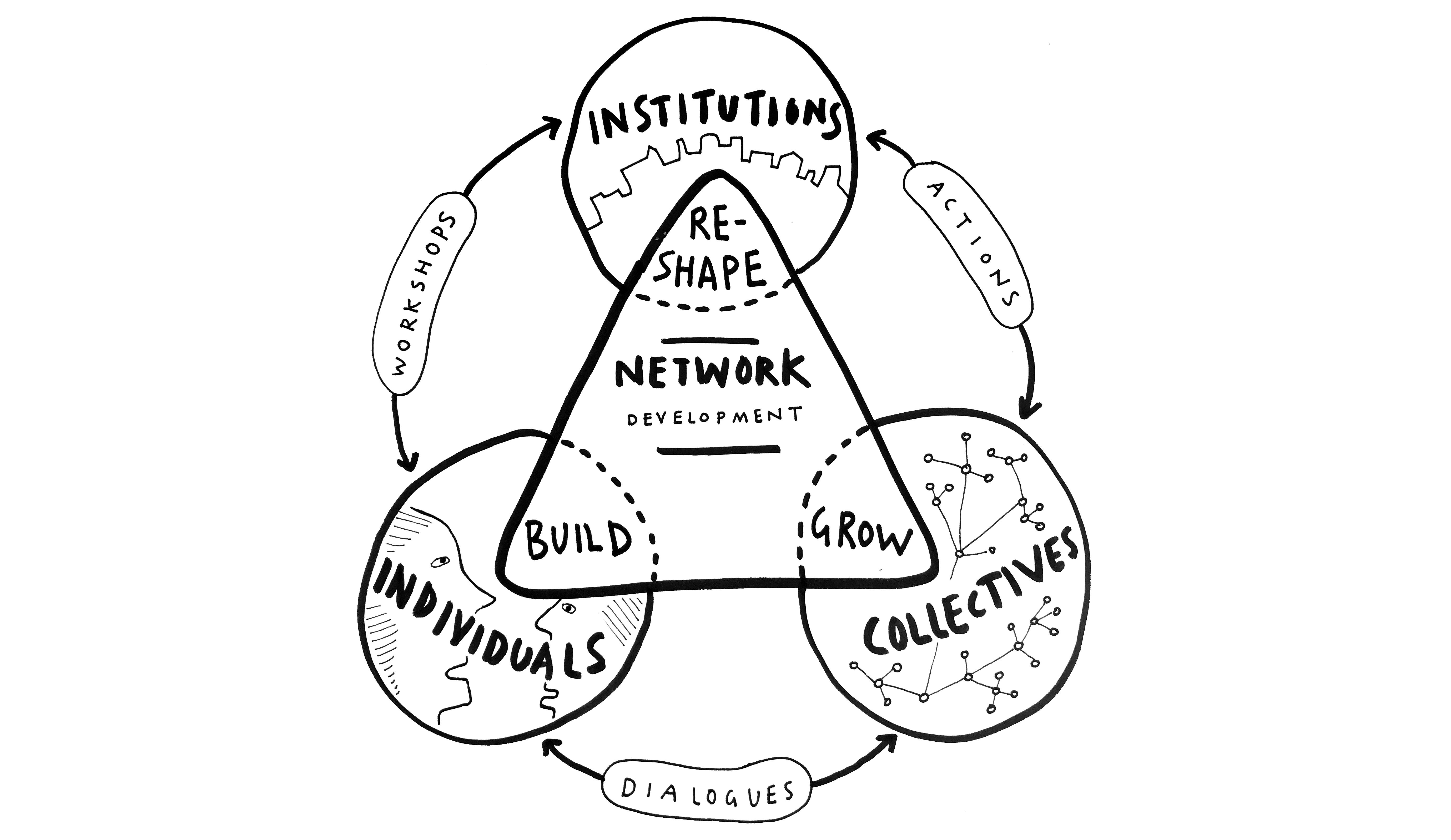

A fictional department resourcing the ‘civil imagination’ as a radical act to reshape realities in poetic, practical and political ways.

Download the DCI Zine for yourself, visit its website, or browse through its content below.

DCI cinema presents: The Department housewarming

Step into the Department under construction

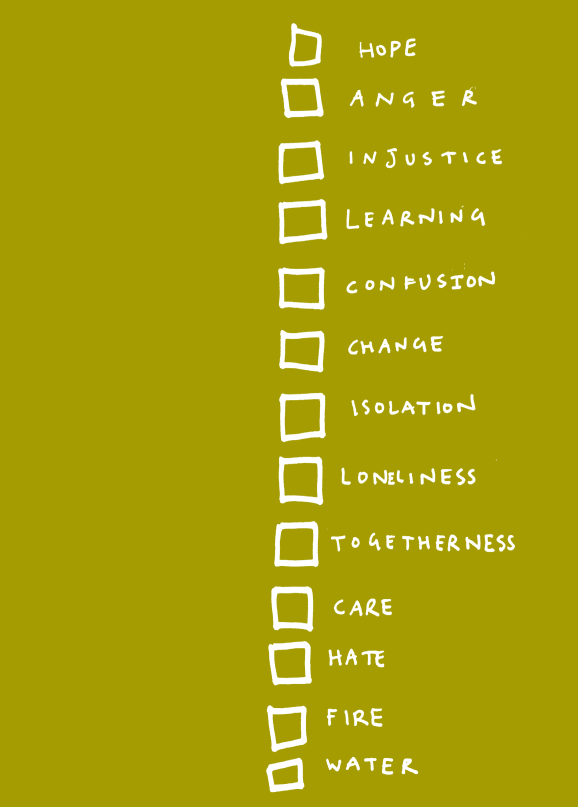

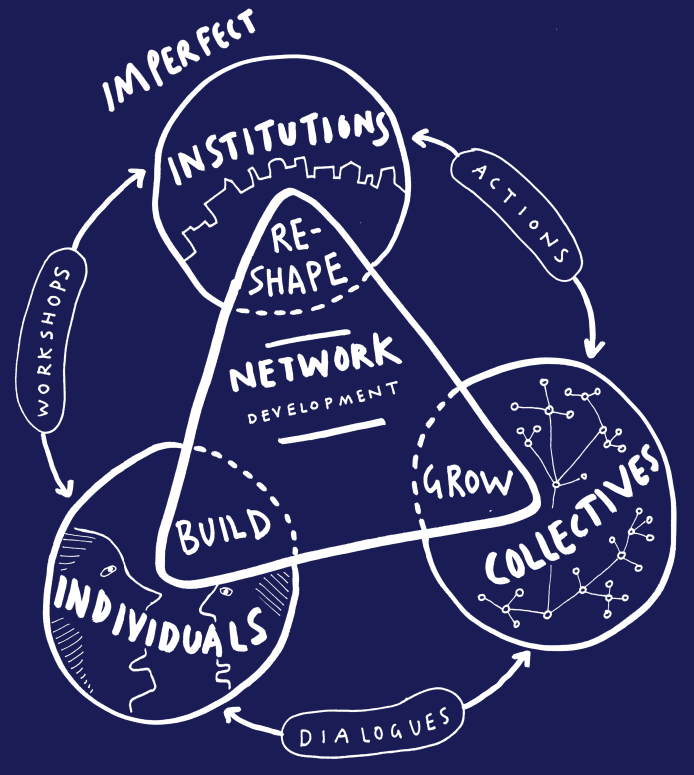

The Department of Civil Imagination (DCI) is a fictional department that utilises the ‘civil imagination’ as a radical act to reshape realities in poetic, practical, and political ways. It is a fiction that sometimes presents itself in the ‘real’ world. It is a possible blueprint, a fantasy, a tool, an umbrella, a fire, a space without walls, a haven, a call to action, a pirate ship, a garden, a rumour, a lake, a gift. The Department currently has ‘branches’ in Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Switzerland, and the UK, active across the arts, migrant activism, global municipalism, radical pedagogy, and cultural re-organisation and is a manifestation of the RESHAPE Network.

To state what is obvious to all of us, at this moment more than ever, there is an urgent need to develop our capacity to discover an otherwise possible together; to purposefully disrupt; to eagerly reach out beyond our comfortable ghettos and make friends with strangers; to forcefully resist returning to ‘normal’; to creatively forge peculiar solutions and unexpected alternatives; and to see what could be but is not yet. The accelerating international sweep of Covid-19, alongside a host of other toxic pre-existing global crises, has taught us that the improbable is now possible. But how do we learn to make the wishful probable possible?

The DCI is a collective and collaborative act. It is not owned by anyone. Instead it is on offer to you as a free and open space for deviance, play, care and re-imagination. In response to Covid-19 and its aftershocks, DCI can be a frame to share and expand as a playful reclaiming of civil and cultural power and a possibility to reimagine our shared futures.

How can we exercise our imagination as a political tool to craft and prototype post-crisis infrastructure, focusing on care and solidarity? How can culture share leadership in reviving civil engagement?

Please enter the DCI, but be aware that this is an open building site so please wear hard hats, look out for loose cables, bits of equipment and tools and rubble lying around, and temporary walls or curtains; there may be trip hazards. Please occupy the lobby, build new rooms, hack the hallways, take it away and make it yours to:

- start a movement working towards transforming, not merely postponing, business as usual across Europe and actually transforming the post-crisis cultural sector;

- create a free and accessible development space to collectively reimagine, skill-up, prototype, distil and share learnings;

- exercise our imagination as a political tool, to shape and share our interconnected problems and interconnected solutions;

- take any or all of what is here and experiment with it;

- create your own rooms responding to whatever urgencies you’re living with.

The DCI once manifested itself via Zoom on 30 May, 2020. This manifestation of the Department explored what ‘rooms’ might first open and assemble – the Critical Care Unit, the Office for Developing Deviance, and the Room of Humid Knowledge – leading those who were present felt passionate about in practice, politics and poetics to actively participate in decorating the rooms. Each room explores some of the ideas that shape it, how this is important for re-imagining post-crisis infrastructure and our role as citizens, and invites some small action of civil imagination.

Respect common values: The Department

A lab to grow our civil imagination.

We are a community of practitioners reclaiming citizenship as a set of skills to live in changing worlds.

We are workspaces, playgrounds, and partners across Europe and the southern Mediterranean.

Working with the arts to exchange knowledge beyond borders.

We grow individual and collective political agency and develop a new culture of politics.

Too often we are told what we are against, rather than what we are for.

We act on our lived experiences, needs and desires.

We ourselves are all the leaders we’ve been looking for.

The team

Chief of Hospitality

Protector of Fairness

Minder of Authenticity

Commissioner of Deviance

Leader of Love

Archivist for Wet Knowledge

Officer of Giant Ears

Care Supervisor

Manager of Liberation

Director of Imperfection

Unmasters of Wishful Thinking

What position(s) should be instantly opened in your organisation?

The Pirate Code

This is the Pirate Code of the DCI. It is a tool for assembling, coming together and instituting. It is also an invitation to imagine what a pirate code of practice could be for your own context.

Inspired by Sam Conniff Allende’s book: Be More Pirate: Or How to Take on the World and Win (Conniff Allende 2018)

Article 1:

Jump with courage

Fall without hurting yourself

Kiss everyone (even with your mind)

Anything goes

Article 2: Make this a family. With openness and intimacy. Bring in your whole self and all your senses, your personal as well as your ‘professional’ self. Bring some humour and playfulness. Trust.

Article 3: Collaboration works. Be generous. Be brave, but kind and humble. Listen as much as you speak. Recognise the labour of others. Speak with transparency.

Article 4: Embrace imperfection. Care about the needs of others. Don’t be judgmental. Respect singularity.

Article 5: Unlearn for real. Let wet knowledge find you. Question if knowledge is power. Trust lived experiences. Exercise your imagination. Be creative without necessarily being productive.

Article 6: Exercise self-governance. Critique, and listen to criticism. Embrace creative conflict. Reinforce shared decision-making and temporary roles. Share resources.

Article 7: Follow the same code outside DCI.

Translation of The Pirate Code to other languages could be found in .pdf.

Conversation with the founders of DCI by VMK

At last, the founders of the Department of Civil Imagination are back together again. After kissing and hugging, long, unapologetically, we raise our glasses to celebrate. We did it! We left all crises behind, and DCI is out there, silently representing the accomplished change, the whisper of the revolution. Back in the old times, before Covid-19, when we first met, who of us would have thought what our coming together, respectfully, humbly, gently and trustfully, would mean for reconsidering our institutions in the arts and cultural sector, and in our practices of care and solidarity? And what imagination could do for us in moments of crises and in-depth transformation?

I remember when the idea of a Department of Civil Imagination was thrown on the table, as an idea, by JLG during our first ‘workshop’ in Edinburgh. We sat in a café where we had escaped to to be among ourselves and to get to know each other better, to build trust and find a common purpose. We had just recently met within the RESHAPE programme and were facing the tremendous task of considering how to reshape our ways of working, our institutions, and ourselves in order to accommodate broader, stronger, more diverse and radical ways of practicing citizenship. We were trying to free ourselves from the weight of the task at hand and the constraints of our minds, and unlearn through poetry and awakened imagination. We were coming up with ideas, without limiting ourselves to the concrete, the useful, the feasible, the realistic. I will never forget how we all instantly laughed at the absurdity and absolute rationale of the idea of a Department of Civil Imagination, and most naturally accepted it as our reference – surely all of us imagining different ways in which DCI could radically transform and subvert our contexts and institutions. We knew we needed it, and yet at the same time we grasped its impossibility… It was too big, too radical, too good to be true…

[VMK] JLG, how did you imagine the DCI, when you brought it up?

[JLG] Over the last year, I have been thinking through a provocation by adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha that ‘all organising is science fiction.’ In that meeting, I think we were trying to articulate a way of organising that could hold us together, and an organising model that would push us towards imagining futures in which citizenship could be repurposed as a set of skills, rather than an instrument of state violence.

So in my mind, I think I was just naming that particular energy in the room to imagine and build alternative infrastructure, whether they be shadow organisations operating in the backroom of national councils, fictional dragons’ dens in which you always got the money, or speculative Saturday schools for the end of the world. It’s not surprising we ended up with a Department of Civil Imagination.

[VMK] During our next meeting in Cluj I proposed another exercise of the imagination. I wanted to see what others see when they think of the DCI. What topics does it deal with and what it is capable of? What could it do for them? So I proposed a game of naming the different rooms in DCI. We had an amazing turnout: The Room of Shared Tentacles, of Cyborgs, of Whispers and Megaphones, of Comfortable Darkness, of Unlearning for Real, of Unlived Experiences, of Hallucinatory Kraftwerks and Bricolage or Eternal Advent Calender are some of my favourites. And the questions that followed… How conscious are we about the languages we use? Why do we use the bureaucratic-sounding term ‘department’, and if it existed what would its architecture look like? Are we building an institution or its antithesis? It was also in Cluj that the concept of wet knowledge appeared. JH, can you tell more and what is its role in DCI?

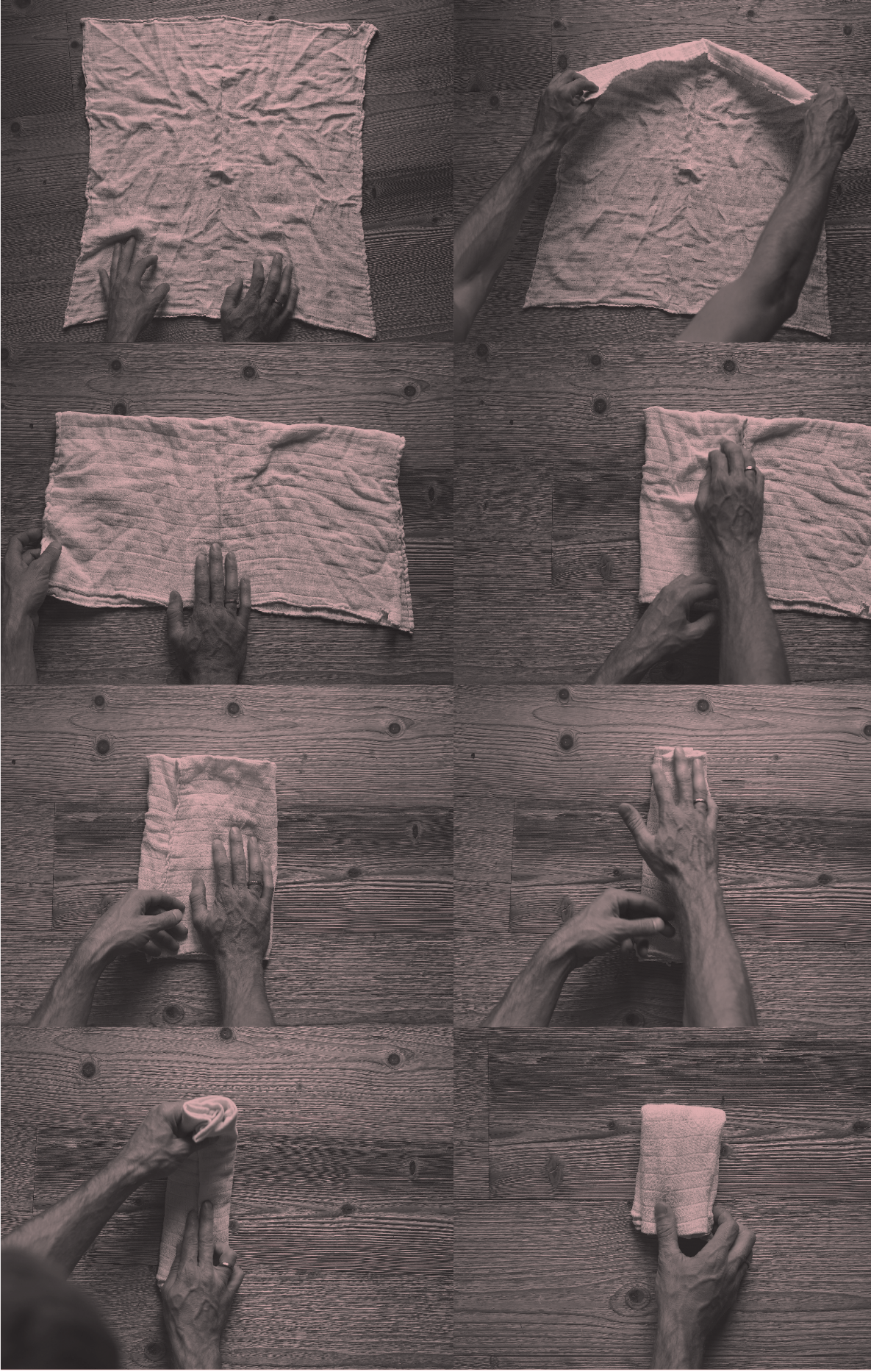

[JH] In institutions you may often find rather ‘dry knowledge’. Knowledge that is thought and taught through dry books and within dry houses. Very often it is accompanied by a person or persons who are aware of their knowledge and are there to inform ‘others’ about it. Then there is what the author Jay Griffiths has called ‘wet knowledge’: knowledge that exists through lived experiences. It is what you do with your hands, your body, mouth to ear, spit to spit, sweat to blood, or with materials, soil and creatures.

I have a longing for humid knowledge.

It is a desire for dry and wet knowledge to come together without any hierarchical relationship, competition, or resistance towards each other. A space where dry and wet knowledge overlay, intermingle, flow into and learn from each other.

For the cultural sector this could mean that the practice and practical knowledge of knowing through doing becomes just as valuable as the maybe more drily learnt institutional knowledge, so that we can start to create a more humid common ground together.

From this humid ground, just as almost all forms of ‘life’ do, we may be able to grow new things. This humid ground for me is the foundation for solidarity and ‘radical tenderness’, ‘a most modest form of love... It appears wherever we take a close and careful look at another being, at something that is not our “self”’, as Olga Tokarczuk says (Tokarczuk 2019). Solidarity and radical tenderness are ingredients needed for honest care.

But of course one of the main questions still remains: how prepared are institutions to ‘really’ change (in a profound way)? Because change needs honest curiosity towards other ways of knowing. Which also means to practice the openness to really REALLY listen – without inwardly thinking that you actually already know the right answer.

[VMK] Such questioning of hegemonies of knowledge/power genuinely leads to the ‘how’. What could be the nature and quality of force that can bring deep, revolutionary change in the way we deal with hegemonial institutions? How could we not be governed (as much)? I believe the C word, which was not so easy to get around, could be a key. Department of what Imagination? Citizenship, Civic, Civil … CO, can you explain why civil?

[CO] Yes, I was bringing in a concept based on Pascal Gielen’s research. We assume that civil is a movement that precedes the civic, the latter being a space and an action acknowledged, institutionalised and therefore regulated by codes and laws… Civil is the wave before, it is the magma before it becomes cold and established... There is a fine line, a gulf between the two, but since the civil is out of any given frame, it can constitute and transform what is civic, the current status. Although both concepts are often used interchangeably, ‘civic’ mainly refers to government, which has ‘civic tasks’ based on which we then have roles, places, and institutions. Civic places are already regulated (by law or otherwise) whereas civil remains open. Michel de Certeau’s thinking lies at the base of this distinction. For him, civic is something established through policies, regulations, or laws. By contrast, civil remains fluid; a space where things are bubbling, roles and rules are yet to be created or subverted.

[VMK] That is to say, DCI is the Becoming, the phase before institutionalisation: the lava before it freezes, knowledge before it dries out… With Covid-19, another C word that has become, next to solidarity, a mantra for dealing with crises entered our discussions: care. During self-isolation, the lock-down, and the unfolding of the crises that followed, which affected the arts sector and live performing arts especially drastically, DCI became the protective and upholding net of care, mutual support, and solidarity. In a moment that clearly revealed the lack of practice in care within our institutions in the arts, the weakness of position and precarity of art workers, DCI became a translocal place to gather and connect, where care was truly heartfelt and lived. It was also when PJ and SW sent us the Be More Pirate book, which gave us new impulses as to how to be deviant, how to rebel in a way that can overthrow the establishment, how to land somewhere better after the crises. MV, can you tell more about why and how institutions should care better, and how the Who cares? workshop can help them to unlearn?

[MV] Care was an issue before the pandemic and will hopefully continue to be so, as a core value in our thinking and practice, after this is over. Caring about people (either members of staff, collaborators, or the so-called ‘audiences’) should be central to visualising the future of our organisations and planning in order for them to be vibrant, relevant and healthy. Ellice Engdahl, Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford, has pointed out a possible way forward for us, where, using our empathy, we may analyse the challenges we face and take decisions which may actually help strike a balance between managing our budget and taking care of our staff, between real value and perceived value, between the global state of emergency and individual professional concerns, between our assumptions and our audience’s needs, between our mission and our messaging. These things aren’t and shouldn’t be seen as incompatible.

The Who Cares? workshop aims to help us all ask the questions that we avoid or were not even aware we should be asking. The world is more diverse and complex than we imagine and the workshop can bring the necessary nuance into our thinking and practice, allowing us to evaluate what we do and how we do it, in the face of multiple societal challenges, under more diverse prisms.

Now DCI is out. It doesn’t cease to amaze me with its adaptability and ability to serve and give hope in a variety of contexts. It works for and in the arts and beyond. It is fuelled by creativity, yet it is not necessarily productive. It is necessarily participative, but definitely does not instrumentalise. It is a lens of exercising institutional critique, however not in practical, but in utopistic terms. In some places it is the department of an institution that transforms its host from the inside in radical ways. In other places, it is a new institution that shows that another way is possible. In some places it is a solidarity network, in others an art agency, or a Sunday School. It sparks the imagination and builds on lived experience.

Rooms to Grow: The Office of Developing Deviance (ODD)

Stop for a moment and ask yourself what is still normal? Do you consider yourself to be normal? Do you even want to be? And together, do we want to go ‘back to normal’ after this global crisis, this apocalypse, which has revealed and unveiled the toxic scale of injustice, inequality, and lack of care that is now normal across the world? If your answer is no, then how do we learn to enjoy being not ‘normal’ – to develop the capabilities and practices of purposeful positive deviance from the norm? How do we resist going back to business as usual? How do we become confidently and delightfully odd and do things differently as citizens and as communities?

> A university created and run by refugees > Marginalised girls empowered in a warzone through skateboarding > Social enterprises built with street children creating a circus > A generation of genocide survivors rebuilding their community through collaborative art, design and architecture > Injustices and niggles aired and shared through joining a complaints choir > A nation-wide exchange economy fuelled by independent music festivals > Young people growing their communities through hip hop > A city guide of favourite places created by local people challenging perceptions > A slum community transformed through art and their indigenous history and culture > A ‘people’s development toolkit’ from a blighted area >

The Office of Developing Deviance is an invitation to nurture and encourage positive deviance –- where people thrive against the norm and, with ethics and aesthetics, have the means to reimagine and regenerate connections; an invitation to people in a community to reflect on, dispute, dream, make, generate, and transform their individual and shared future. It is an enticement to development misfits and inbetweeners to strengthen their courage to disrupt and collectively build our understanding and practice of creative ‘deviance’ in doing development (international, urban, civil, community, and human development) – a place where the difference of ‘artists’, the context of community and the potential of development can come together in an intelligent and creative interface to experiment, foster new attitudes and habits, codify practice, reimagine metrics, and reset norms.

‘If the arts are to create ways for us to look into our past, make sense of our present and build imaginations for our collective futures, arts leaders must themselves become disrupters to enable processes of creation that transform our realities.’

– Arundhati Ghosh (2019)

Often misunderstood or dismissed for being different, ODD people, and their values, principles and practices, may be beyond what is considered by many to be ‘normal’.

normal dull conventional straight humdrum hierarchical timid customary orthodox neat obedient mainstream workaday compliant average prosaic risk-averse sensible certain predictable cowardly fixated clean unexceptional standard inflexible safe conservative habitual technocratic routine run-of-the-mill conformist predictable acquiescent familiar normal

ODD is aimed, first and foremost, at those who purposefully deviate from the normal or accepted ways of doing development, who have different ways of seeing, feeling, thinking, and imagining and who work with these capabilities to shape creative solutions within and across communities. These are primarily, but not exclusively, cultural and creative practitioners. And then there are the essential ‘intermediaries’ who act more like enablers, connectors, fixers, or entrepreneurs, rather than acting like bureaucrats, and alongside them, a small group of funders, institutions, and policy-makers who want to experiment and to understand and support unorthodox and deviant solution making.

odd deviant punk eccentric piratical idiosyncratic playful disruptor risk-taking maverick off-centre misfit subversive outlandish imperfect fluid aberrant adventurous rebellious queer rule-breaking outlying curious optimistic irregular non-conformist transdisciplinary mutinous iconoclastic silo-breaking misfit empathetic game-changing weird bubble-bursting futuristic activist magician atypical off-the-wall irregular ground-shaking peculiar abnormal care-full outre mischief-maker odd

Purposefully embracing and acting with ‘deviance’The Positive Deviance Initiative is to go beyond the usual frames, narratives, practices, and habits of existing institutions and the rigid technicalities of development. The notion, and practice, of deviance conventionally has negative connotations – anti-social, disobedient, destructive, criminal and so on – but deviance has a more positive place in development. Deviance is also a means by which communities can creatively and collectively release the multiple blockages of the system, locally and globally.

Art, artists, culture and creativity (understood in the broadest possible sense) are powerful sources of positive deviance because they start in the subjective and specific context, constantly imagining alternatives and growing possibilities.

The crisis: Sadly, we all know the script. It’s no surprise that, in response to such chaos, contradictions and complexity, so many of us feel increasingly disenchanted and disengaged and, most of all, powerless to do anything about such universal challenges. We make the mistake of looking to others, to the ‘powerful’, to do something about changing the system.

The system: The world spends €£$ billionsAid spending alone by OECD figures for 2016 is over £100bn and was at an historic high. on ‘development’ for citizens (international aid, charitable giving and foundation funding, infrastructural initiatives and regeneration investment in countries, cities, and communities). This money normally focuses on solving problems, usually identified from afar by big institutions and departments engineering universal best practices and technical assistance to deliver them. But this is a moral as much as a technical field. It’s about imagination, possibility, and engagement in shaping a future life we want to live.

The technical and ethical error of the current system is to strip away a lot of the beautiful complexity of human development in an attempt to reduce the risk of things going wrong and costing too much – in money or reputation or timescale. These are normative, practical and political obstacles to change.

The more we create one-dimensional frameworks of certainty and risk aversion and attempt to make a very subjective and complex field into an objective and technical one, the more we inadvertently create systems of disengagement. When people are disengaged there is a slippery slope towards blaming others, not taking responsibility, not caring about the consequences, and treating others with less moral concern and empathy, and ultimately validating violence or abuse towards others. This leads to the opposite of development – withdrawal, decline, shrinkage, and all too often conflict and war. This cost is ultimately too high but we continue to pay it, perhaps because we don’t know how to stop.

There is a growing practice, emerging from the margins and intersection of culture, development and community activism, that could be the beginnings of a new model or ecosystem of development. These ‘positive deviations’ (the exceptions to the rule that innovate against the grain) are places we can look to for reducing the long term human, moral, social, political, and economic cost of a lack of capability to be part of shaping the future.

How does this deviant development practice work, who helps to make it happen, how is it grown around the world, and how can it influence institutions to really shift? Where is the practice that can help shape this shared space? Where are the positive deviants creatively working to make this possibility a reality?

The ODD is an emerging marginal shared space of learning and action where the resources of development, the urgency and community of activism, and the skills of cultural and creative practitioners can come together to create a more engaging, empathetic, enchanting, and effective future.

Artists, creative and cultural thinkers and makers bring a set of perceptions, skills and ways of working that can help to create this new space. Below are a few characteristics of ‘artists’ (understood in the broadest possible sense) that can make them valuable positive deviants for development.

- Artists are neophiles – they have an insatiable appetite for finding and creating new connections, for inventing and reinventing. Art means changing the meaning of things or creating new meanings.

- Artists are humanists – they are experts of the subjective and observe human desires, needs, emotions, and behaviour with a high degree of empathy for human realities and vulnerabilities.

- Artists are skilled makers – they create discourse by doing. Art combines excellence with significance, it has both a physical dimension (virtuosity in crafting) and a meta-physical dimension (connecting to broader meaning).

- Artists are curious – they retain a unique sense of possibility, wonder, experimentation and ‘what if’ not constrained by established ways of doing and being.

- Artists are intuitive – information is knowledge but intuition is pre-emptive knowledge that combines data with experience. Intuition is constantly tested, experimented, and prototyped to explore and validate it.

- Artists embrace ambiguity – by design, they deal with things that are not measurable and can’t be easily quantified. In stark contrast to mechanistic and technical models, they seek uncertainty and open-ended questions, and can hold two opposing truths in their mind.

- Artists are holistic, interdisciplinary thinkers – art can stimulate and challenge our understanding of the world around us and within us. Artists are masters of mash-up and mix who can connect the dots and take things out of their original context.

- Artists care about detail – the specifics of any work or action are vital and central to the success of any artistic project, be it location, materials, staging, light, sound, and so on.

- Artists thrive under constraints – they often have to work with ingenuity and resourcefulness. In fact, these constraints might even stimulate their creativity to create new value with minimal resources.

- Artists do things ‘in spite of’ and are autodidacts – their work responds to something they feel the need to do or create, not in response to a set of KPIs (key performance indicators) and they teach themselves the skills they need to make it happen.

- Artists are storytellers – they tell stories with their work: in many ways that is their work.

- Artists are collaborators – most artists increasingly need to be involved with multiple sectors and disciplines with a humility to reject the myth of the lone genius and to pursue cross-border approaches.

- Artists are passionate and patient – their work and life are impossible to separate. They often face rejection, but are tenacious in patiently creating the right relationships and contexts to make things happen.

- Artists are makers of ideas and solutions – they see the world as it could be and bring fresh perspectives. Sometimes they are the fools who speak the truth, have ‘insane’ ideas, and make change happen.

‘Like art, true innovation has the potential to make our lives better. It stretches our souls and combines the exploration of possibilities with action. It connects and reconnects us with deeply held truths and fundamental human desires; meets complexity with simple, elegant solutions; and rewards risk-taking and vulnerability with lasting value. However, businesses must refrain from making art a disciple of innovation – and they must refrain from designing innovation as a mere process. That is perhaps the golden rule artists and innovators have in common: only if they allow ample space for new things to happen that could happen, will they happen.’

– Tim Leberecht (2012)

ODD space for new things to happen

The Office of Developing Deviance starts with an understanding that our cultures (in our organisations, communities, families) have accepted ways of doing things – the norm. ‘Normal’ behaviour is the nearly universal means by which individuals in society solve given problems and pursue certain priorities in everyday life. Sometimes this is valuable and cohesive but sometimes ‘normal’ doesn’t work, it can be a tyranny that constrains our ability to imagine alternatives and make positive changes. Perhaps sometimes, maybe now more than ever, we need to develop unconventional behaviour or eccentricity and learn to become positive deviants.

Psychologist David Weeks studied eccentric people and deems there are several distinctive characteristics that often differentiate a healthily odd person from a regular person (Weeks and James 1995):

- Enduring non-conformity

- Creative

- Strongly motivated by an exceedingly powerful curiosity and related exploratory behaviour

- Idealism in the sense of wanting to make the world a better place and the people in it happier

- Interested in and have mischievous type of humour

- Are non-competitive and do not need reassurance from society or from other people

Interestingly, he also believes that eccentric or positively deviant people are less prone to mental illness than everyone else.

ODD Instruction Number OneOhOne

The first invitation by the Office of Developing Deviance is to start to ask ourselves what happens when we act in a ‘normal’ manner or accept the tyranny of convention, often against our own better judgements and instincts. We feel the pressure to conform.

This invitation will take only five minutes of your time but is a 101 starting practice to developing deviance.

- Take a moment, alone or with colleagues, friends, or family.

- Think back and try to remember a situation when you felt constrained or oppressed by the ‘norms’ or expectations around you so that you either had to do something that you felt was wrong or you did not speak out against something that you felt was not right. We’ve all been in such difficult situations many times.

- How did you feel at the time? Angry, ashamed, unsure, frustrated, compromised, uncertain, cowardly, nervous…?

- How do you feel today, thinking about it?

- Now, take a moment to think about what could have made a difference to how you behaved in that situation. What could you have done differently? It could be something that you want to leave behind or something new that you want to have or do or be. It could be something really practical or something more poetic or magical that breaks the spell of tyranny.

Here are some examples that were shared during the inaugural meeting of the Department of Civil Imagination and the Office of Developing Deviance.

- A magic wand to make everyone else stop.

- I would have listened, and listened more and not pretended I knew the answer.

- Reprogramming Attitudes Switch Button.

- Stubbornness as a quality tool.

- Distancing myself from the process and analysing it with people who weren’t part of it.

- Someone who would stand behind and support, as simple as that!

- An ability to ignore from an early age my conformist upbringing.

- More courage.

- An intention transformer that turns competitivity into collaboration.

- Turn off the mouths, turn on the ears.

- A living pause button.

- Silence to cut through the noises.

- Time.

- An ally with magic powers.

Hold onto that break in your behaviour and use it to be braver next time you need to be odd. Oddness does not mean opposition or unkindness. It is a sensitive eccentricity to make new things possible in the practice of changing the world for the better (what some call the Just Transition or System Shift).

Rooms to Grow: Humid Knowledge Library

The Humid Knowledge Library

The Humid Library

The House of Humid Knowledge

The Sharehouse

In institutions you may often find rather ‘dry knowledge’. Knowledge that is thought and taught through dry books and in dry houses. Very often it is accompanied by a person or persons who are aware of their knowledge and are there to inform ‘others’ about it. Then there is what the author Jay Griffiths has called ‘wet knowledge’: knowledge that exists through lived experiences. It is what you do with your hands, your body, mouth to ear, spit to spit, sweat to blood, or with materials, soil and creatures.

The Humid Knowledge Library is a space where dry and wet knowledge can come together without hierarchical relationship, competition, or resistance towards each other. A space where dry and wet knowledge overlay, intermingle, flow into each other and learn from one another. Here practical knowledge of knowing through doing becomes just as valuable as the maybe more drily learnt institutional knowledge, and, together, a humid common ground is created. From this humid ground, from which almost all forms of ‘life’ come, we may be able to grow new things.

Of course this process needs a lot of humility too. It needs learning and unlearning. Therefore, the Humid Knowledge Library is run by the Officer of Giant Ears, a specialist in True Listening, aided by the Synthetising Agent, who mingles together the wet and dry components to feed into each other, and understand their interdependence. The task is not easy, as humid knowledge is hard to keep. It needs to be sprayed gently and often, to maintain the right humidity and humility. Also, it needs a carrying agent, a human, as it is nurtured by lived experience and cannot be kept in books. It has an irresistible drive to be shared, gently, physically, orally.

Please help us improve our services!

We are in perpetual becoming and transforming, together with all of our agents, human and non-human, without whom the library and humid knowledge could not exist. Humid knowledge needs us! It needs our coming together, to develop our capacity for listening and synthesising, so we can provide a better ground for keeping and passing the precious humid knowledge on. Some members of the DCI have already started experimenting with various ways of how this humid knowledge can be acquired, shared, captured, stored, lent, or sorted. Next to inventing and imagining new formats, rooms, and practices that could replace the (institutional) ‘library’, we are also curious to think about transforming the already existing (institutional) libraries (Or is this an illusion? Is the ‘the physical space of a library’ – similar to museums and theatres – too charged anyway? Are the walls too dry and too thick?) How would these libraries need to evolve so that they can accommodate humid knowledge? What forms, formats, rooms, and practices have you been working on to keep the humid knowledge spreading? Do you know how to turn dry knowledge humid and humil? Do you have the right tool or format by which to mix and synthetise dry and wet knowledge or to keep and pass humid knowledge on? Write us at departmentofcivilimagination@gmail.com and tell us how the Library could work, feel, look, smell, sound for you.

Rooms to Grow: The Critical Care Unit

Welcome.

This room directs our attention to the act of caring, especially in difficult times, when the future is far from clear. On care as a political gesture, its potential and on the policy of care.

Why do transformations call for care? What type of care? Whose care? And for whom?

This is a room for self-observation and a care-full critique of how we as individuals and institutions operate. In times of extreme urgency, this room encourages us to institute new practices of care and practice new caring institutions.

The story of Care

This is the story of Care

Care lives in a world that is fast. With a cost-minimising boss biting at her heels, Care rushes wherever she goes. She wakes up in the early morning darkness to rush from one bedside to the next, one family’s child to another, around a delivery route, back to this kitchen sink and this fruit picking ground. Care works hard. Her arms and legs ache and her fingers are bleached.

On her morning bus journey, Care sometimes passes larger than life billboards of Self-Care. It’s Care’s older cousin – looking glamorous and fit, healthy and well, strong and empowered in a matching yoga outfit in a chrome kitchen staring back at her. Care and her older cousin have stopped talking to each other. Funny to think they are part of the same family, but are leading such different lives.

Care daydreams on this bus. It’s her only pause and time to reflect. On a world where often pouring your heart and love into something other than your own life is considered naive, immature, silly, non-sense. Care often feels invisible, or blocked, as if surrounded with walls of glass – unable to reach out. Even obsolete.

The bus stops, and Care walks down a path into the woods to her first job. But what awaits her is not a three-storey home waiting to be cleaned, but a blaze on the second floor; an incredible fire that is licking its lips and consuming her bosses’ home. The heat from the flames make her sweat. She stares at this incredible force. She stares at this incredible dance of energy and smiles.

Care meets the fire

Fire is a solitary creature, beautiful from a distance. That’s why it plays at keeping people away, with threats and smoke. It is a smoky creature that tosses and breaks up every single line it says by coughing, it’s grumpy and gruff with a dishevelled tuft that contains multitudes of dreams.

It plays with appearance, seems hard but if you come closer you can feel the temperature of the sensual dreams it hosts. It is a threat and an opportunity. There is something beautiful in the challenge, why don’t we reward the ability to show open wounds?

Many want to defeat fire, to sedate the sparkle and there is even a head money on it. But others see the beauty of the purification it has, the crackling overture of a white page for a possible future.

Care is not afraid of fire; logs are wooden arms in which she lulls and sings fire lullabies. She grows and feeds the flames, flames are screams scraping the skies, nails on a chalkboard for teenager riots.

Care wants to comfort and caress the fire with a hug, but the weight of her body embraces the flames and ends up extinguishing the fire. At least for a moment, enough to turn into ashes that will be a mother again of new lives.

Care is a cocoon to incubate and transform, to turn obstacles into opportunities, to trigger unpredictable outcomes that can reshape current scenarios into unforeseeable desirable futures.

Care falls into a trance and memories flood into her body

Memories of lived lives and lived wisdom come to her from all directions.

From a time when there was enough community and care for everyone.

When care-for-self meant care-for-the-other.

When people realised that the collapse was inevitable, that the collapse was needed.

When a pandemic spread across the world again and again and again.

When non-disabled, heterosexual, white citizens realised how other communities had crafted strategies to survive.

When care was valued.

When care was dismissed.

Care looks closely at the embers and decides to slow down.

Care plans.

Care trains.

Care plants seeds.

Care prepares the spare bed.

Care embraces not-knowing.

Care welcomes the extended family.

Care redefines borders.

Care learns a new language.

Care cooks for herself and others.

Care opens the door.

Care knits a pair of socks for all who feel cold.

Care walks away from the house, towards the sea. Today she has the morning off.

The Story of Care was presented at the launch of the DepARTment of Civil Imagination on 31 May 2020

An Introduction: Care in our cultural organisations

Crises normally increase the visibility of certain lingering issues; they increase our awareness. As a result of this awareness, taking action becomes something more definite and urgent – at least, in the minds of some people. In this respect, the 2020 pandemic is no different.

The issue of care has definitely taken centre stage recently. Seeing large (and, in some cases, wealthy) cultural organisations quickly disposing of their education and ‘non-core’ staff as a result of the lockdown and suspension of activities and events, shocked many around the world. At the same time, the fact that some organisations rushed into rescheduling the part of their programming that was cancelled or making content available online raised very relevant questions: Who are we (cultural organisations) doing this for and why? How essential are we to others? In what ways? And who is essential to us? (Simon 2020; Spock 2020).

Care was an issue before the pandemic and will hopefully continue to be so, as a core value in our thinking and practice, after this is over. Caring about people (either members of staff, collaborators or the so-called ‘audiences’) should be central to visualising the future of our organisations and planning in order for them to be vibrant, relevant, and healthy.

Using our empathy as a guide in analysing the challenges we face and taking decisions may actually help strike a balance between managing our budget and taking care of our staff, between real value and perceived value, between the global state of emergency and individual professional concerns, between our assumptions and our audience’s needs, between our mission and our messaging (Engdahl 2020).

Caring is the right thing to do. Caring means creating more justice. Caring allows for challenges to be faced collectively and more successfully, making the world a safer place for all.

The spreading of Covid-19 has been threatening the notion of community with the rhetoric of immunity. The shadow of otherness became bigger and bigger, like an imaginary monster on the wall when night falls. The effect was a fragmentation of the social fabric and the social contract in which digital intimacy is the only form of togetherness. The public, the public space and the institutions play a crucial role in how we will live together.

The killing of George Floyd by a white police officer in the US has sparked unrest all over the world. Unlike what happened in 2014, when the killing of various black citizens by the police was considered irrelevant by most cultural organisations, in 2020 those that remained silent were few. Their statements, though, were in many cases met with criticism by both members of staff and other citizens, who considered that the organisations that issued them had actually done very little to fight racism and racist practices, both internally and within wider society (Greenberger and Solomon 2020; Murawski 2020a; We See you, White American Theater).

There is often a wide gap between theory and practice and this fact is currently being heavily criticised and contested. Society asks for greater accountability and this has to start from within.

To make this possible, cultural organisations need to look at themselves and ask themselves some hard questions, the right questions. This process will have to be facilitated by each organisation’s leadership, as it holds the power. Leadership should show the ability to deal with the discomfort caused by honest institutional critique. But in order for the exercise to be truthful and efficient in bringing about change, it must involve all members of staff.

Criticism and self-criticism are also signs of care: we care to make things better.

Nevertheless, this is not just about criticism. Thus, this exercise of institutional critique is not just about identifying what is wrong (i.e. lack of care), but getting into the active mode of creation, proposing concrete solutions for the institutional failings. It is also about understanding what allows for this to happen and what kind of values and practices it takes for this to change.

We have a collective responsibility for this and everyone can and should care, and ask ourselves: who do I have the responsibility to care for?

Who Cares? A workshop in caring

To learn, together, how to grow a culture of care, the Critical Care Unit is creating a workshop. Here we share the first steps of our work. It is to be prototyped, tested and developed initially within local affiliations of partners of RESHAPE.

If you are curious and interested in participating in a workshop, please contact us at departmentofcivilimagination@gmail.com.

Who is the workshop for? For institutions of all kinds and in the field of arts and culture, across disciplines, sectors and continents, big or tiny, new or established - the essential motivation is the desire for change, to be more responsive, more urgent, more open and caring.

How does it work? With this workshop DCI invites you to its Changing Room. Although it is about your workplace, your institution, please wear something that you feel comfortable in, but would probably never wear at work. In the Changing Room you can lay down old and worn-out ways of doing and try on some new ones, or combine the old ‘outfit’ with some new elements. It is a space to get naked, partially at least, where you can check the labels of your ‘practices’ and priorities and if they (still) fit your values – and your context.

Step 1: Make your mind up to change and get in touch

As we all know, real change can only come from within. So if you really truly feel the need for change, and if you are ready to change yourself, to listen and make compromises, please contact us ASAP! Introduce yourself to the DCI via a subjective self-portrait, including a reflection on the (hi)story of your organisation, and a mapping of power structures and dynamics within your organisation and in your wider local context. Describe why you feel the longing and need for a change/shift.

Step 2: Sketching a self-portrait

Once we have connected, a member of the DCI will help you work out the fine tones in your self-portrait with you, including all the different voices that may exist in your organisation. For this purpose, we will institute the Room of Whispers and Megaphones. Here we will:

- map the power structures and dynamics within your organisation (through methods such as emotional cartography and social mapping) and the wider local context;

- articulate and clarify your basic values;

- voice those of each individual longing for change (or not) within your organisation.

Based on this complex self-portrait the DCI will reach out to a local artist (maybe also a DCI member) to do step 3 and 4 together with you.

Step 3: Friction (& coming-out)

Here we will, in collaboration with a local artist, collectively deconstruct the self-portrait and start shifting power dynamics around.

- learn to be deviant through the special tools of DCI’s Office for Developing Deviance;

- collaboratively write your organisation’s own pirate code (the DCI’s pirate code can be used as an example);

- come-out to the ‘public’ with your pirate code by making it visible/audible: for example by projecting it onto the walls of your building, by recording it and playing it on loud-speakers in front of your building or in the hallway or toilets of your organisation.

Step 4. Reconciliation/Shape-shift

Here we will, in collaboration with a local artist, uncover:

- What needs to shift if you want to apply the pirate code within your organisation?

- What new/different ‘rooms’ do you need to create to do so?

- What roles and practices could be invented? (for example, with the rooms and titles exercise).

What will you learn from this workshop?

- Gaining an understanding of the relationships between artists, staff, collaborators, audiences, neighbourhood and place, especially how the work of caring for these relationships is currently distributed.

- Acknowledging where the work of care is invisible because of gender, race and/or class, and how to take steps in valuing this work appropriately.

- Brainstorming and making collective decisions on adopting care as a formal value, and implementing a caring practice that is true to the organisation’s vision and mission.

- Asking who needs to support the care-full critique of your institution. Ensuring all staff members, including freelancers and out-sourced workers, alongside artists who have a relationship with the institution, are able to feed into a transparent process.

- Remembering that care and solidarity are not just new buzzwords and require protocols to ensure accountability, regular questioning, and governance.

What do you need to bring along?

To make something clear from the beginning: there is no fast and cheap and good solution to your problems. These three variables simply do not add up, they are the neoliberal promise that has brough our world the constant crises we experience. In order to take one seriously, you need to sacrifice another one.

- Time: change rarely happens overnight. We don’t have the magic wand that will transform your organisation fast and effortless. To do this process, we will need time. Time to reconsider, and time for the change to hold. The process, from beginning to end, should take several weeks, with the workshop sessions and the time between.

- Money: please regard the DCI as one of your extended departments, where people also work for their living, just like your colleagues. DCI and its agents will help you in exchange for a fair compensation of the time and energy invested – this of course will depend on your possibilities and context. Remuneration will be negotiated while working out the self-portrait.

- Deliberation and courage: In order to change, you need to be ready to get naked, to say sorry, to fight, jump and fall, without hurting yourself (that much).

Imaginary rooms to grow

The Department of Civil Imagination is an ever-expanding space of opportunity.

As a fictional space, not an institution, it can grow ‘rooms’ to meet our needs, dreams, urgencies, and contexts.

These are some of the imaginative spaces that the guests of DCI’s foundation party explored.

Shelter in generous solidarity

‘I was wishing for a room for comforting, listening and learning, that could be generous and have food for everyone at all times, and I wanted a room to start over again, together, one that is non-judgemental, and that is filled with the smell of sincere apology…’

Togetherness training

‘Togetherness training is actually something I needed a lot during confinement, and I guess we all had, because suddenly we were very distant.’

De-acceleration accelerator

‘This idea was of having a de-acceleration accelerating chamber, which is a place where de-acceleration can be accelerated. It is a room for ecological transition, de-acceleration, de-growth or slow-growth. It is a room where all people participate based on principles of solidarity and collaboration for mutual support, and share resources such as ideas, methods, goods, artefacts, networks, money.’

Urban symbiotic witchcraft

‘I was just imagining how we could reimagine our city lives and interconnect more the elements that make our cities, and rethink knowledge as a magic craft, like witchcraft, almost not knowledge anymore. With magic gestures, magic potions, magic ways of being together and including all the elements, human and non-human, we would invent more natural, interconnected, symbiotic ways of living together.’

Healonarium

‘About four weeks ago I was in an accident. I got hit by a guy in a moped and I broke my elbow and my hand, and I have been in bed ever since, so this room I am in has actually been my healing place. I decided to call it a Healonarium, as my partner who has been taking care of me is a landscape architect and he likes to save plants from the street and he puts them in special spot on the balcony that has lot of Sun, and he calls it the Sanatorium. So I just thought that this room has become a Healonarium for me.’

Lost washing choir

‘I imagine a space, where you could come in, the floor would be very soft, and you would hear loads of voices, like so many small speakers, voices of people sharing the things they have lost. You could go in there and you could write down what you have lost, or do a drawing and add it onto the walls. There would be two small separate rooms, in one there would be a little microphone, where you could record your losses, and then it would automatically become part of the big choir of voices. And there would be a second small separate room, where someone sits, so that if you really want to share your loss with someone in person, you could also do that. It is about the idea of how do you actually start to find the voice to express something, and how do you not feel so alone with that.’

Social muscle gym

‘Here we try to train back our capability, ability to stay together, but rather than pumping muscles, we try to make them more elastic and long, so we are able to react and be flexible and be responsive to others and the situation we jump into. And I think subscriptions are open to all of you.’

***

We would like to ask you to support us with your imagination and your lived experience, as well as your needs, desires, challenges. What rooms would the Department of Civil Imagination need to grow to meet your needs, support you in your challenges, intervene in your urgencies and help expand your practice?

Think about it either from a very personal point of view, and/or from a perspective concerning your community, your city or your context. Just take it as a playful exercise.

***

‘We can best be revolutionaries when we turn to be institutional. ... The true test is not so much becoming a critic, but becoming a proponent of formats that could actually be viable. That is what “learning how to be institutional” meant to me. Like Buckminster Fuller said, instead of criticising the system, just create a new system that makes the previous system irrelevant.’

– Pablo Helguera (2013)

Developed in the framework of the RESHAPE trajectory Art and Citizenship.

* An Vandermeulen contributed to the early thinking and development of this work.

** Ella Britton contributed design thinking and development to this work.

This text is licensed under the Creative Commons license Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International.

References

Desai, Jemma. 2020. “This Work Isn’t for Us”. https://sourceful.us/doc/337/this-work-isnt-for-us--by-jemma-desai. (institutional critique regarding diversity)

‘MASS Action Toolkit’ (transformation from the inside out – more equitable and inclusive practices in museums), https://incluseum.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/df17e-toolkit_10_2017.pdf.

Mingus, Mia. 2019. “Transformative Justice: A Brief Description”, Leaving Evidence, January 9, 2019. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2019/01/09/transformative-justice-a-brief-description.

Petz, Sarah. 2020. “Former Employees of Canadian Museum for Human Rights Say They Faced Racism, Mistreatment”, CBC, June 10, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/canadian-museum-human-rights-racism-allegations-1.5606075.

‘Pirate Care Syllabus’, https://syllabus.pirate.care.

Radical Support Collective, https://www.radicalsupport.org.

The exhibitionist, https://www.theexhibitionist.org.

Thorne, Sam. 2017. School – A Recent History of Self-Organized Art Education. New York: Sternberg Press.

We see you, White American Theatre, https://www.weseeyouwat.com.

Wilson, Emily. 2020. “At This Museum, Education Staff Prove More Vital Than Ever during Pandemic”, Hyperallergic, May 12, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/563185/asian-art-museum-education-covid-19.